That the parts of a piece of music, a work of art, a novel or poem can inspire more than the whole won’t likely come as a surprise for those of us who see a story in everything. I was lucky enough to catch two exhibitions in London recently. While they were completely different in nature, what they had in common was that they were prime examples of the parts being greater than the whole.

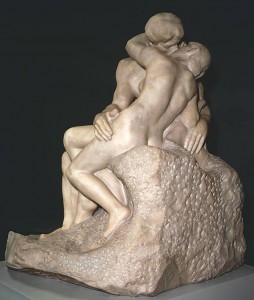

The first exhibition was Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greeceat the British Museum. Presently some of Rodin’s most famous works are being exhibited side-by-side with a selection of the Elgin Marbles. Though Rodin never made it to Athens, his work was profoundly inspired by the art from the pediments that had once adorned the Parthenon.

“No artist will ever surpass Pheidias … The greatest of sculptors, who appeared at the time when the entire human dream could be contained in the pediment of a temple, will never be equalled.” Auguste Rodin

“The entire human dream … contained in the pediment of a temple.” Has there ever been a better description of what we as writers, as storytellers try to do in the pages of our work? And after seeing a photography exhibition at the Museum of Londoncalled London Nights, I couldn’t keep from noticing that theme played out over and over again.

Rodin’s temple with its pediment of the human dream is his Gates of Hell, a work I knew nothing about before the exhibition. The Gates of Hell, was to be a representation of Dante’s Inferno. Sadly only a small clay replica of that masterpiece was on display. For a better view and more details about Rodin’s Gates of Hell check out the YouTube link.

The sculpture was commissioned in 1880 for a museum that was never built. But Rodin was so pulled into the effort, so inspired by it, that he continue to work on it on and off until his death in 1917. Many of his most famous sculptures, including The Kiss and The Thinker (who originally represented Dante sitting in the tympanum of the sculpture) were inspired by and taken from his original work.

“None of the drama of Life remained unexplored by this earnest, concentrated worker … Here (in The Gates of Hell) was life, a thousand-fold in every moment, in longing and sorrow, in madness and fear, in loss and gain. Here was desire immeasurable, thirst so great that all the water of the world dried up in it like a single drop.”

Rainer Maria Rilke (Briefly Rodin’s secretary)

The following weekend I found myself at the Museum of London standing before two images that, like Rodin’s Gates of Hell, invited me to dwell on the intriguing details and secrets of the parts, rather than the whole. Since there was no photography allowed, I ended up frantically taking notes on my phone. The images were both temples, of a sort, both attempting to contain the human dream in their “pediments.” One was a photograph from Rut Blees Luxemburg’sLondon: A Modern Project. The image, taken in 1999, is of a London high-rise apartment building in what looks to be a lower middle class neighbourhood. I was pulled in because I could see into people’s windows, into their lives. I wondered about their stories; the bicycle sitting on the balcony of the top floor, the Christmas lights visible in several windows, the dark flat with “shadow monsters” from childhood dreams pressing to the balcony windows seeking entrance. At the center of the photo is a stairwell illuminated in garish florescence, bisecting the building from top to bottom. It’s the only apparent connection to the stories in the apartment framework. This building is a container for the human dream played out in a thousand different ways with a thousand different outcomes.

The counter to Blees Luxemburg’s high-rise of flats is Lewis Bush’s high-rise office building. The particular photo that drew me was taken at night when the offices should have been deserted. The image itself is slightly distorted in perspective, a view from below, but not from the ground. The glare of light reflected at certain angles obscures the view in some of the floor to ceiling windows. When I looked closer, I realized there were a few people still inside. And none of them looked particularly happy – though that could have been my imagination, because to me, this was a story waiting to be told. This “pediment” was a perversion of the human dream. There was nothing personal about it and very little human. Perhaps that’s why I was so drawn to the few people who were there. What was written on every face, at least to my observation, was the terrible cost of living that dream. Here are a few of my frenetic notes.

Soul captured in a photo. People still in the high-rise office at night? Why? What are their stories? What’s the guy at the bottom looking at? The one looking out the window, does he see the photographer? Would anyone stuck in the building believe him if he told them?

The one with hair hanging in his face — what’s he looking at on his screen? He looks frazzled. Woman with head down on desk? Why? And is there a man sitting in the reception area? Why’s he there? What’s he waiting for?

Is there a guy in a priest collar???

Is that a gym?

Reflecting on the two photographs now, it seems interesting to me that there were no people visible in any of the windows of the flats, as though they might be able to hide in their private world. But there is nothing private about the office high-rise. The photo seems all about being exposed in the darkness.

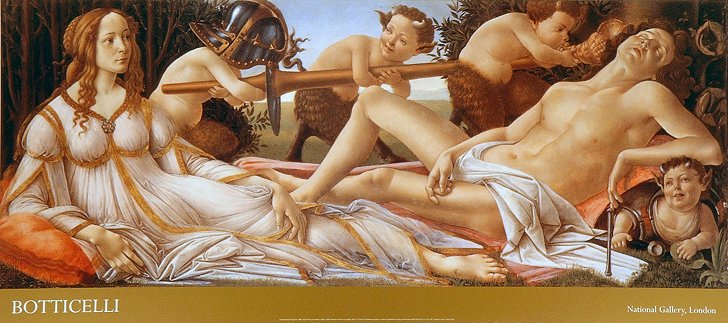

The enclosures, the containers that hold the stories we long to tell, are high rises, homes, tunnels and caves underground, spaceships, battles being fought, beds being fucked in, and long roads travelled. We write them voyeuristically, as we look into the windows of our experiences and beyond. The stories we pen are the pediments for human dreams. They contain our Gates of Hell, our gods and goddesses and their epic toying with humanity. They contain our monsters in the dark and our unexplored lives. They will remain always only in the pediments where we can see them, and take them out, and explore them, and be uncomfortable with them, or aroused by them, or frightened by them, or totally pulled in to their tale. Their tale is always our own retold, and yet never quite like we’d planned it, certainly not the way we lived it out. What holds us within the framework are the once upon a times and the happily ever afters, the what ifs and the whys. What keeps us coming back for yet another look is the hope inspired by a dream kept alive when death looms ever larger.

It’s an overwhelming task we take on as writers, as artists. How could we endure it or

explore it if all we ever saw was the high-rise or the temple? It’s too much to take in.

It’s the secrets in the pediments, in the office at night, in the curtains not quite completely drawn that keep us telling our stories. In our imagination, in our urge to create, we’re drawn to the pediments for the dreams, the vignettes. We’re pulled in

by the questions that reveal themselves and startle us into realizing what they might mean. But we linger there because of how they surprise us when they’re suddenly the center of our focus — those things we didn’t notice before.

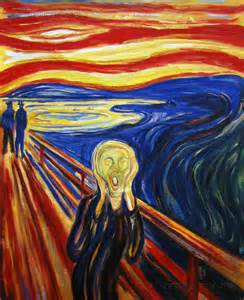

post from the archives on one of my favourite topics — sex and chaos and their effect on story. Enjoy.

post from the archives on one of my favourite topics — sex and chaos and their effect on story. Enjoy. in almost any kind of novel. The world is not a static place, and especially the world of story should not be static. Happy endings are called happy endings because they are at the end. They follow the chaos and happen when the story is finished. There is no more story, or at least none the reader wants to follow. It’s the chaos that pulls us in and keeps us turning the pages, and when that chaos is directly tied to sex, hold on to your hat!

in almost any kind of novel. The world is not a static place, and especially the world of story should not be static. Happy endings are called happy endings because they are at the end. They follow the chaos and happen when the story is finished. There is no more story, or at least none the reader wants to follow. It’s the chaos that pulls us in and keeps us turning the pages, and when that chaos is directly tied to sex, hold on to your hat!

One theory is that kissing evolved from the act of mothers premasticating food for their infants, back in the pre-baby food days, and then literally kissing it into their mouths. Birds still do that. The sharing of food mouth to mouth is also a courtship ritual, and birds aren’t the only critters who do that. Even with no food involved the tasting, touching and sniffing of mouths of possible mates, or even as an act of

One theory is that kissing evolved from the act of mothers premasticating food for their infants, back in the pre-baby food days, and then literally kissing it into their mouths. Birds still do that. The sharing of food mouth to mouth is also a courtship ritual, and birds aren’t the only critters who do that. Even with no food involved the tasting, touching and sniffing of mouths of possible mates, or even as an act of