It was my pleasure to be a part of the wonderful Guildford Writer’s Group for several years and getting to know the very talented writer, Amy Kernahan, was one of the highlights of that experience. At the time, Amy was writing her wonderful travelogue, Orion is Upside Down, so once a fortnight the whole group got to experience Amy’s amazing pilgrimage, with her father, to Antarctica. I couldn’t be more pleased to introduce you to Amy and the story behind Orion is Upside Down. Welcome, Amy!

Antarctica was once the very essence of inaccessibility. One of its poles (the Pole of Inaccessibility) is named so. Did you know that Antarctica is home to more than one pole? It’s home to more than one Pole as well, assuming Arctowski Base s occupied. Several years have passed now since I visited, but the Polish research station on King George Island is still going.

Antarctica was once the very essence of inaccessibility. One of its poles (the Pole of Inaccessibility) is named so. Did you know that Antarctica is home to more than one pole? It’s home to more than one Pole as well, assuming Arctowski Base s occupied. Several years have passed now since I visited, but the Polish research station on King George Island is still going.

The working research station may or may not be on the itinerary, but Antarctica is now firmly on the tourist trail and sojourns there are as common in print as they are becoming in actuality. So why is my journey, made only shortly after the first so-called ‘cruises’ to the White Continent, and my journaling of it any different? What qualifies me? To my knowledge, no Antarctic chronicler in print has ever seen their own island home reflected in the islands of the sub-Antarctic. But for the Gulf Stream, the Outer Hebrides, where I was born and raised, would, like South Georgia, be permanently robed in glaciers. As it is, they are a twin to the Falklands. Thus I have an affinity with the land itself.

Antarctica is more than the penguins.

Antarctica is more than history.

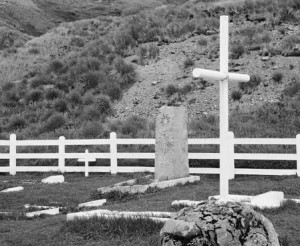

Been and gone is what is called is called the Golden Age. (But who’s to say the best is not to come?) Sir Ernest Shackleton, in whose Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition’s wake the bark of my journey sails is an archetypal giant of polar exploration. But alongside my awe of Shackleton, I have the simple affection of a shared heritage with Thomas MacLeod, Able Seaman on board Endurance, Shackleton’s ship. Shackleton, known for bestowing nicknames upon his crew called him ‘Stornoway’ after his wee… my wee… our wee home town.

So there are my credentials: Antarctica herself and one of her lesser-sung heroes are a part of what I call ‘home.’

The Peregrinatio is the ancient Celtic search for one’s true home. Orion is Upside Down chronicles mine.

Blurb:

This sea story from the bottom of the earth takes the reader on a philosophical voyage through many realms, religious and secular, mathematical and poetic, natural and mechanical. Something akin to a Scottish Bill Bryson, Amy Kernahan, who was born and grew up on the Isle of Lewis, the largest of the chain of islands off the northwest coast of Scotland, sets out with her travelling companion, her father, to journey in the Antarctic and follow her dreams of seeing, and even standing in, the places where Sir Ernest Shackleton had been.

Casting Shackleton in the role of Virgil to her Dante, she follows his trail through the ice fields around the Antarctic Peninsula, a vision here on earth as hellish as the frozen Lake Cocytus at the centre of Dante’s Inferno. Along the way, the might of the sea, and the glories of the Antarctic set Amy pondering themes of Judeo-Christianity, seeing Antarctica as a remnant of Eden, unpopulated by both mankind and sin. The mathematics of nature reveals itself to her, and she is awed by the prophetic soul of Coleridge and his Ancient Mariner.

Amy has set out on her journey believing it to be a pilgrimage to Shackleton’s grave, but as she sojourns beneath striking southern skies where even the familiar is alien, she realises that she is on another more spiritual pilgrimage, called by the ancient Christians of her homeland peregrinatio, the search for what they called ‘the place of one’s resurrection’ or true home. The outcome, although perhaps not surprising, is not quite as clear cut as it might have been.

Excerpt:

We were surrounded by giants. Nootaikok, the Inuit god of icebergs, and his court. Tradition describes him as ‘large and very friendly.’ I wondered which space-time continuum that was in. Certainly not this one. I had mourned the results of his handiwork since I was six years old. Nordnorge lay motionless, like one prepared for martyrdom, unarmed before the executioner, yet daring to bring her petition to a god not renowned for mercy, whatever tradition might say.

Of course, the couple of hours of outward inactivity were taken up with the crew’s preparations for landing, out of sight down in the car deck, but standing out on deck beneath the lifeboat that had offered so little shelter as we rounded Cape Horn, in the stillness that seemed to be as much a part of the place as the mountains and the water were, it was easy to imagine that the ship was holding parley with the god of the ice, bargaining for the safety of her passengers. Nootaikok acquiesced and the landing began, but the little boats, that the previous evening had gambolled around like puppies, seemed subdued. They waited patiently for their charges under the lee of Nordnorge’s hull, huddling in to the mother-ship for protection.

Be careful, she warned them. If your propellers hit the ice…

Ice littered the bay. As well as the bergs, many of them level with the ship’s superstructure, the water teemed with brash ice, up to three feet exposed, and the comically named ‘bergy bits’ that filled the taxonomic gap between brash and true bergs, anything over fifteen feet. And then there were the infamous growlers, barely visible submerged ice that lurked just beneath the surface, like the submarines of some hostile alien power.

The ice here is glacial, ancient. I have heard people say of Titanic, ‘How could crashing into ice sink a ship?’ No one would doubt that crashing into a rock could sink a ship. Glacial ice, the stuff icebergs are made of, is harder than rock. It is not frozen water, it is compressed snow, the ice at and below the surface the oldest, the hardest, compressed over aeons by the mass of hundreds of feet of snow-becoming-ice above it as it makes its slow, unrelenting journey to the sea, gouging its path out of the rock, tearing away the surface as though it were topsoil. Anyone who doubts its destructive power need only look at the fjords of Norway, their sheer cliffs dropping to the sea – ice did that. Destruction that creates.

Tomas helped us ashore again, but he didn’t need to hold the Polar Cirkle boat’s nose quite as firmly as he had at Deception Island; she was making no attempt to bolt.

‘Welcome to Neko Harbour,’ he called out. ‘Our first landing on the Antarctic mainland.’

Close to our landing point stood a little wooden hut, painted bright red to make it stand out against the natural white, a white so bright it seemed almost unnatural. The hut was a refuge erected by the Argentineans in 1949. And what a refuge it must have been to anyone who had run the gauntlet of ice that guarded the Harbour. But now, like the crumbling remains of the station at Whalers’ Bay, it was home only to penguins and seals.

The Harbour is named after a Norwegian factory ship which operated there between 1911 and 1924. Looking out into the bay I tried to picture her (tried because I didn’t really know what a factory ship looked like) lying there surrounded by the ice, which tolerated her with disinterest as it did now another Norwegian vessel. Nordnorge looked suddenly small, disappearing behind one of the aquatic white mountains that patrolled the bay.

Thou rash intruder on our realm below.[i]

They stood at the gates of Dis, the threshold to the nether-hell, Dante and his guide. No way to go but onward, for no-one can retreat out of Hell. You can’t go back the way you’ve come. If you do, you may leave Hell, but Hell will not leave you.

And as the demons at the gate appraised them with scorn, ‘Thou with us shalt stay,’ they say to Virgil.

No.

But did Shackleton, man of words and eloquence and frustrated poet himself, Virgil now to a reluctant Dante, ever think that perhaps he would?

The guide turns to his charge.

‘Have no fear, no matter what they do to me. I’ve been here before.’

Is that why we journey through Hell? So that once we’ve been there and know the way, we can guide another through?

The paradox of Antarctica began to manifest itself. A place that could be Eden, unsullied, un-fallen, could just as easily be Hell.

Or vice versa.

This terrifying place, with its monstrous inhabitants, was equally the last haven of peace and innocence. But we were banished from Eden.

This is the ice’s world, and we really have no business being here.

About Amy Kernahan

Amy was born and brought up on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides, but she’s now an ‘economic migrant’ to the South East of England, where she work as an assembly, integration and test engineer for a company building small satellites in Guildford, Surrey. That’s the ones up in space, not the dishes on the sides of buildings.

A fascination with technology led her to choose a career path that she believed would bring her to its cutting edge, gaining along the way a Masters in Aerospace Engineering from the University of Glasgow and studying for a time at the prestigious Ecole Nationale Supérieur de l’Aéronautique et de l’Espace in Toulouse. But the reality is somewhat different and whoever said the space industry is glamorous has never worked in it!

When she’s not writing or hidden away in a big white scrupulously clean laboratory wearing a silly hat and static-deflecting overalls, Amy does milage. She is now saying ‘never again’ to another marathon, but her year wouldn’t be complete without her trips to Cardiff and Liverpool to run in those cities’ half-marathons. And she likes to trek the long-distance paths of around a hundred miles, five to six days walking. In a world where we can hop on a plane and be almost anywhere within twenty-four hours, Amy likes to travel in the most primal, human way she can. Ironic, perhaps, for someone who spent four years of her life learning to design aeroplanes.

But Amy’s first love has always been the sea. You don’t get much more primal than that.

Find Amy Here: www.amykernahan.co.uk

Get your Copy of Orion is Upside Down Here:

Links to Amazon:

Paperback:

Kindle:

Waterstones:

http://www.waterstones.com/waterstonesweb/products/amy+kernahan/orion+is+upside+down/8613945/

[i] Dante, Inferno VIII, 90 tr Dorothy L. Sayers